Review

Oberhausen: Leaving the Cinema

Adam Pugh uses the 64th Oberhausen International Short Film Festival to show that cinema is essential today, it being one of the few remaining social structures to enable public assembly

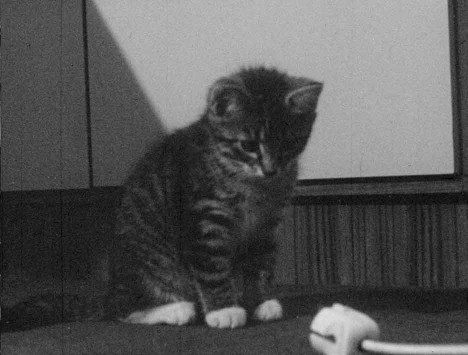

Rolf Thissen Warum Katzen? (Why Cats?) 1969

What is striking about Oberhausen, a post-industrial, working-class city rebuilt extensively after the Second World War, is its enduring sense of the civic. With much in common, architecturally, with the New Towns movement of 1950s Britain, its neat public precincts and leafy boulevards testament to inter- and postwar modernist resolve, it stands apart for its youth centres, unprivatised transport network and the prevalence of anti-racist murals and graffiti.

The materialisation every May of an outwardly quixotic, tenacious and stubbornly committed short-film festival in such a place would be incongruous were it not for the fact that the festival shares the same firm postwar footings as the city that hosts it. And over the festival’s 64 years, the two appear, at least to an outsider, to have become encoded into one another’s existence, the measured, meticulous yet geometrically fanciful brickwork of the city’s fantastic 1930s town hall somehow an instruction for what was to come, the programme of Europe’s most singular film event similarly unlikely and wonderful.

This year’s theme, ‘Leaving the Cinema: Knokke, Hamburg, Oberhausen’, traced a line of dissent among filmmakers frustrated with the strictures of conventional cinema to three key festival events in the late 1960s: 1st Hamburger Filmschau; Exprmtl 4 in Knokke, Belgium; and Oberhausen itself. The eight programmes’ thematic sweep, which charted the political and formal tropes which came to identify and be identified with the ‘Anderes Kino’, or ‘Other Cinema’, was expansive and frequently fascinating – and aided by presentations by several of the group’s key protagonists, Lutz Mommartz and Klaus Wyborny among them.

The architects of the Other Cinema wanted, as Alexander Kluge postulated, ‘to leave yesterday behind’, and this meant shunning a cinema culture tied to commercial imperatives, patrician values and intellectual timidity. There were cracks in the Other Cinema movement almost as soon as it was formed, with Harun Farocki, when he was a student, disrupting screenings in Knokke that he perceived as apolitical. A fervid time of possibility and renewal, and the fact that it coalesced around festival events, remains pertinent to a contemporary landscape in which it is these structures, in time not space, which are able to sidestep conventional constraints.

A sense of the political prevailed nevertheless. One screening in ‘Leaving the Cinema’ threatened to provoke its audience to do just that, following a documentary by Irm and Ed Sommer of Hermann Nitsch’s 7. Abreaktionsspiel, 1970, itself a taunt to the conservative Catholic community of the day. An orgy involving disembowelled animals, viscera and buckets of blood forced into human orifices, a functional crucifix and penetrative sex with a strap-on phallus, the film was followed by Rolf Thissen’s Warum Katzen? (Why Cats?), in which the artist dismembers a cat arduously using what appears to be a bread knife with apparent glee; the programme was as tough as it gets, though still marginally more tolerable than having to sit through a Wes Anderson film.

Where the theme could have been more successful was to situate its specific history more actively in relation to the present and possible future of cinema. The festival’s tendency towards drier and less discursive modes of enquiry made this harder to do: a propositional approach would perhaps have wrested more from the theme. And there are wider areas that the festival still needs to address: in particular, the format of the daily ‘Podium’ discussions, which are in danger of becoming so passive and didactic that they occlude their own purpose; and the very low representation of women on those panels is a recurring problem which shows no signs of having been tackled. That many of the central protagonists of the Other Cinema were male (with accompanying adolescent ideas about the inclusion of women in their films; where they did appear, it was to provide close-ups of their genitalia) should be no impediment to the interpretation of that history by women: indeed, it would serve only to activate it further and help in part to solve its rather wooden exegesis.

Elsewhere in the festival, quiet and thoughtful work by the Romanian artists Mona Vatamanu and Florin Tudor, and a superb screening of work from the Slovak Film Institute, stood out as memorable, alongside three significant new strands introduced in 2018 to unfold over the next three years. Of these, ‘re-selected’ is an archival project looking at cinema as a history of copies, slight in stature but a beguiling prospect; ‘Labs’ presented work from artist-run labs; and ‘Conditional Cinema’ focused on performance-based work.

Curated by the affable and generous Mika Taanila, ‘Conditional Cinema’ articulated an ambition to interrogate the form of cinema itself. A highlight was Taanila’s re-presentation of Owen O’Toole’s terrific A Filmer’s Almanac, 1988, an invitational Mail Art project which aimed to include a reel a day for the year, each by a different artist. The result read like a crowdsourced Chris Marker film, and was a riot of colour, sound and unlikely cinematographic contraptions: music sourced directly from FM radio, twin Super 8 projectors mounted on lazy susans, images creeping across one another and onto walls and ceilings.

Ultimately, bringing radical histories to the cinema itself, having it function as a space for exchange and speculation, only confirms that space as essential. Where the Other Cinema was a reaction to the perceived ossification of cinema culture at the time, the dispersal and disassembly that this provoked was possible only because there still remained a strong social body which functioned in part as the stage for political hegemony. But the atomisation of the intervening 50 years and the near-complete liquidation of civic instruments means, ironically, that the cinema is now one of the few remaining social structures which enable public assembly.

To move from mere assembly to the creation, once again, of a zone for the exchange of ideas is now the task at hand. That this function is currently limited is no impediment: the apparatus exists. As the festival in Oberhausen has continued to demonstrate, to leave the cinema would be a fatal mistake: today’s most radical course of action is precisely to return to the cinema and demand its recuperation as an intellectually vital space.

64th Oberhausen Film Festival took place 11-16 May 2018.

Adam Pugh is a writer, curator and designer based in Newcastle upon Tyne, where he runs Projections, the artists’ moving image programme at Tyneside Cinema.

First published in Art Monthly 418: Jul-Aug 2018.