Feature

Ad Men

Anna Dezeuze on the appropriation of art by advertising

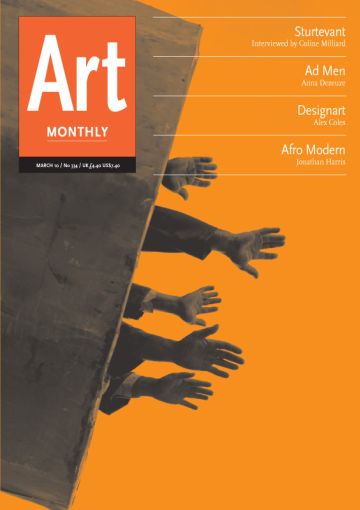

A flurry of internet discussions has surrounded Toshiba’s new space chair advertisement for wide-screen televisions, focusing in particular on its striking resemblance to British artist Simon Faithfull’s Escape Vehicle no.6, 2004, most recently on show in the artist’s exhibition ‘Gravity Sucks’ at the British Film Institute last summer.

Both the ad and Faithfull’s video feature a chair, tethered to a large weather balloon, being launched into the sky, rising over 30km off the ground, hovering over the surface of the earth and exploding under atmospheric pressure. The launch is filmed by cameras attached to the balloon, and in both we can hear the regular bleep of the radar signal transmitting the footage to viewers on the ground.

When Andy Amadeo, the ad’s director and creative director of the publicity agency Grey London, was asked in an interview on National Public Radio about his relation to Faithfull, he responded without hesitation that the artist had been ‘part of the team’ – a claim that the artist himself has refuted. And when the Toshiba-Grey team repeatedly boast, in The Making of Space Chair (available on YouTube), that they have tried ‘something nobody tried before’ and that such ‘leading innovation’ constitutes ‘Toshiba’s nature’, one wonders if the inability to tell the truth is a genetic flaw in the company’s innovatory ‘DNA’.

Of course, such disputes are not new and can in fact be traced back to the earliest interactions between advertising and visual art. When the manager of the Pears soap company visited Victorian painter John Everett Millais to discuss using his painting of a little boy blowing bubbles as an ad, the artist, who was by no means averse to other commercial applications of his art, nevertheless ‘protested strongly against this utilisation’ of his picture, but realised that ultimately he ‘had no power’ to prevent them using it ‘in any way they liked’ (as they had purchased the painting, along with the copyright, from a third party). Pears’s rival in the soap market, Lord Lever, did not for his part feel the need to obtain permission from the artist William Powell Frith to reproduce a painting that he owned, The New Frock, 1889. In a letter of protest, the artist told of his surprise when he encountered his picture of a little girl showing off her new dress in an illustrated paper, re-titled So Clean!, in order to promote Lever’s Sunlight Soap.

While copyright laws today would probably allow both Millais and Frith to contest such blatant appropriations, conceptual artists continue to experience the surprise, frustration and resignation of their Victorian predecessors. Artists like Faithfull or Christian Marclay find out about such plagiarism when friends send them a YouTube link. Marclay had been approached by Apple, and had declined to work with them; in contrast, Faithfull has stated that he did meet with Grey to discuss a possible collaboration in the context of a live performance of Escape Vehicle no.6 for the ‘Gravity Sucks’ exhibition, which would have involved beaming the live footage into one of the BFI cinemas, and later ‘an edited version for TV, functioning as an artwork/advert’. The event remained unrealised, but the process involved in creating Faithfull’s work was replicated by Toshiba without his participation, much in the same way as the Apple Hello ad that launched the iPhone in 2007 directly borrowed from Marclay’s Telephones, 1995, the comical device of mounting in sequence a range of film clips showing fictional characters answering the telephone. Apple has done this kind of thing before, negotiating with US photographer Louie Psihoyos to use his 1995 ‘Wall of Videos’ image, The Information Revolution, 500 monitors, for the launch of its Apple TV product in 2007, then pulling out of the deal and making its own version.

Just as Millais found himself forced into a defensive position against supporters who mistakenly believed that he had painted Bubbles as a soap advertisement, conceptual artists fear unfair accusations of complicity and opportunism. After Honda created their acclaimed Cog advert in 2003, using the same chain-reaction narrative as Peter Fischli & David Weiss’s well-known film Der Lauf der Dinge (The Way Things Go), 1987, the artists complained: ‘We’ve been getting a lot of mail saying “Oh, you’ve sold the idea to Honda.” We don’t want people to think this. We made Der Lauf der Dinge for consumption as art.’ Even more pernicious in the debates following Frith’s letter of protest in 1889 was the suggestion by some critics that the kind of work he was producing lent itself to such commercial use, and that his own ‘degradation’ of the medium through the choice of trite, popular subject-matter was to blame. Lord Lever himself enjoyed boasting of the ease with which he could adapt paintings such as Frith’s to commercial purposes.

Long after the end of debates over genre painting, a similar logic is mobilised again in relation to Conceptual Art. It is because their works are reducible to simple ideas, it has been suggested, that conceptual artists are so easy to ‘rip off’ – indeed, by protecting ‘expression’ rather than ‘ideas’, copyright laws seem to privilege visual appearance over concept. When in 1998 Volkswagen stole Gillian Wearing’s concept for Signs that say what you want them to say and not signs that say what someone else wants you to say, 1992-93, however, the difficulty of clearly demarcating ‘idea’ from ‘expression’ was revealed. Since both the artwork and the ad showed people holding handwritten signs to set up a revealing contrast between the sign-holder’s appearance and his or her statement, this visual similarity suggested that they shared the same concept. However, Volkswagen had in fact turned the concept on its head by hiring actors to hold up signs that said precisely what ‘someone else’ wanted them ‘to say’, unlike the spontaneous, and sometimes painfully honest, confessions by strangers whom Wearing had met in the street.

Such commercial appropriation is often justified by attacks on the originality of the models that ‘inspired’ the ads. Surely, it is argued, Fischli & Weiss did not invent chain reaction, familiar to any schoolchild lucky enough to have a good physics teacher or a predilection for Roadrunner cartoons. And who is Marclay to complain when he himself should be sued by film studios for his own plagiarism? Indeed, it has been suggested that the grey area in the copyright laws may in fact be responding to the avant-garde tradition of artists engaging with the popular culture of their time, and serve to protect artists such as Marclay when they use copyrighted material in their work. Such discussions ultimately serve to obscure the real issue at stake here: the uneven playing field between the artist and the advertisers, who can indeed use contemporary works ‘in any way they like’ (as Millais had noted) in order to earn vast amounts of money by distorting the ideas of the original. Consequently, when hearing that Faithfull had in fact approached Grey London, many of us will certainly be wondering how the artist could have been unaware of the risks involved in opening that can of aesthetic and advertising worms.

It remains interesting, nevertheless, to consider the reasons why such contemporary artistic practices have appealed to the publicity industry, and what can be learned from a comparison between the ads and their models. Since humour became a dominant advertising strategy some time around 1960 (pioneered by Volkswagen among others), a synergy has developed in the use of irony and comedy in television, film and contemporary art. Beyond their humour, Faithfull, Wearing, Marclay and Fischli & Weiss share a basic interest in everyday life, and the use of simple, amateur-like techniques to reveal its hidden or underlying features – whether the deep fears and desires of ordinary passers-by, the dramatic potential of the routine phone call, or the ways in which an everyday chair can suddenly be launched into space and tyres can nudge each other up a slanting ladder. That advertising trades in the everyday will come as no surprise; what sets these specific adverts apart from many others is the simplicity and economy of their means. Like Fischli & Weiss, who created a sense of wonder using commonplace objects in The Way Things Go, the Honda ad garnered admiration because it was made in real space, with real objects and much real time and effort – at great expense. Similarly, Amadeo emphasised that the Toshiba ad ‘had to be real’ precisely because ‘the world we live in’ is full of computer-generated images. Ads such as Cog or Space Chair are praised because their images are not produced through digital manipulation; crucially, the sleek, illusionist effects of new technologies are exactly what has been countered by a trend in art since the 1960s that emphasises everyday, concrete realities, and explores failure, error and imperfection in the artists’ very ways of being and making.

Such interests are of course only superficially replicated by the ad men – as Jeremy Millar has pointed out in relation to Cog, ‘one would hardly expect to see technology being portrayed as temperamental’ in an advertisement for a presumably safe and reliable car. As Mia Fineman, writing in the New York Times observed, in the ad, unlike the messy The Way Things Go, ‘everything works as it should, automatically, sometimes even invisibly, with no pause, no hesitation’. Mr Honda may have wisely stated that ‘success is 99% failure’ (as the ‘making of’ video for Cog informs us), but the ad’s gloating voice-over is smug, a far cry from Fischli & Weiss’s mocking self-consciousness. Similarly, in the Toshiba ad, Faithfull’s schoolboy experiment has been considerably cleaned up. The Nevada desert makes for a more dramatic and cinematic setting than the Hampshire countryside; the strings holding up the chair in the ad are almost invisible and do not get tangled up in the awkward mess of knots which turns Faithfull’s chair upside down. Most importantly, eight cameras were attached to the chair, thus providing different angles, and the high-definition footage that they captured was actually rescued after the fall, whereas for Faithfull ‘Escape Vehicle no.6 ... was a one-way mission. The camera and chair came back to earth but were lost forever – all that remains is the signal’, a signal whose shaky, erratic quality hauntingly deteriorated until it ended in total blackness.

Thus Faithfull’s fascination for what happens at the ‘edge of space’ becomes, in the Toshiba/Grey rhetoric deployed in the ‘making of’ film, the pursuit of ‘innovation’ for novelty’s sake, a world record for ‘the highest advert ever filmed’. Human aspirations to escape from the laws of gravity are reduced to a celebration of what the Grey London managing director, quoted in the Daily Telegraph, piously describes as the client’s ‘bravery’ as they ‘take the risk’ of engaging in such a ‘unique’ project. Indeed, the flying chair appears as the perfect image of our contemporary capitalism, described by Zygmunt Bauman as thriving on short-term tactics of risk-taking and evasion, and ultimately aspiring to an ever-mobile, ever-elusive weightlessness.

Faithfull’s childish frustration at being ‘tethered to this mundane realm’ (summarised by the sulky ‘gravity sucks’ motto) may resonate with this new ‘lean, buoyant, Houdini-like capital’ as well as the ideology of progress that drives Toshiba, but his melancholy orchestration of failed utopias constantly undermines any real belief in the power of speed and technology (he describes one of his earlier ‘vehicles’ as ‘truly pathetic’). The explosion of the chair in Toshiba’s ad is redeemed by the high quality of the footage, which is misleadingly presented as a live transmission signal. Where Faithfull’s project description invites us to imagine ourselves sitting in the ascending chair, doomed to die from the cold and lack of oxygen, Toshiba returns us to the safety of our living-room armchair, watching television. ‘Armchair viewing, redefined,’ perhaps, but armchair viewing nonetheless: a passive experience with little space for uncertainty or playfulness, let alone quixotic aspirations or ‘heroic failure’.

Anna Dezeuze is a postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC.

First published in Art Monthly 334: March 2010.