Feature

Activism as Art

Activism is not an add-on says Tom Snow

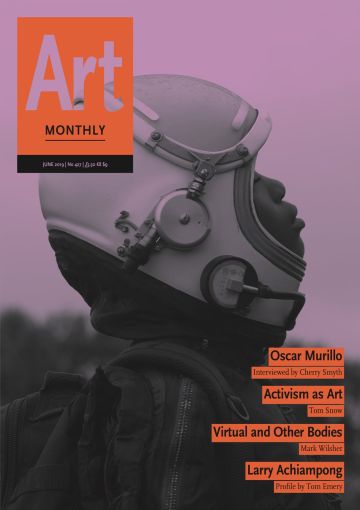

Liberate Tate, The Gift, 2012, wind turbine blade delivered to Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall

It is time that museums recognised activism as central to critical art practices by individuals and collectives, such as Liberate Tate, PAIN, and BP or not BP?

A spectre is haunting the museum – the spectre of decolonisation. In recent years the alliance of artists and activists attempting to exorcise corporate patronage from cultural institutions has gained traction. To some extent we are witnessing the expulsion of those making cynical philanthropic sponsorship arrangements with museums and gallery spaces. This association with contemporary art has helped those donors finesse their public image, their sponsorship providing moral cover for tax breaks and subsidies. The end of Tate’s relationship with BP in 2016 was a significant achievement, insofar as years of agitation by the artist-activist group Liberate Tate seemed to be finally yielding results (see Dave Beech’s feature ‘To Boycott or Not to Boycott’ AM380). That is, unless you asked Tate, which blamed the ‘competitive business environment’ for the decision, rather than giving credit to the creative and collaborative labour of Liberate Tate (Artnotes AM395).

When it was revealed that BP contributed an average of just 0.5% of the institution’s annual running costs, following legal pressure by Brendan Montague with support from anti-oil activist group Platform, Tate’s long-term insistence on the oil giant’s necessity to its operations was doubly confusing (Editorial AM394). So much for PR.

More recently, photographer Nan Goldin has spearheaded a campaign for museums to cut ties with the Sackler Family Trust because of the family’s ownership of the US pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma, which manufactures the highly addictive opioid OxyContin (Artnotes AM425, 426). Goldin has suffered from addiction to opioids herself, almost overdosing when being prescribed OxyContin, and has participated in Sackler-funded exhibitions and museums in the past. Among Goldin’s and other activist strategies has been the staging of die-ins at major museum spaces, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Guggenheim in New York; these were not dissimilar to Liberate Tate’s 2011 protest performance Human Cost in the Duveen Galleries in Tate Britain, which involved a naked figure being drenched like a helpless sea creature in oil, one year after the BP Gulf of Mexico oil disaster. Lying on the floor of the Guggenheim earlier this year, Goldin and other activists were surrounded by flyers that read ‘Sackler lie, people die’, which were dropped from the building’s internal helix, an act which further recalled the recent creative protests of the Gulf Labor Coalition (Books AM394). In 2014 GLC dropped phoney dollar bills targeting the museum’s franchise role in the construction of Saadiyat (Happiness) Island in the UAE, a project that has resulted in the deaths of migrant labourers.

In fact, the strategy also brings to mind ACT-UP’s protests at the New York Stock Exchange in 1989 during the AIDS epidemic, involving faux dollar bills reading ‘Fuck your profiteering. People are dying while you play business’ designed by Gran Fury (see Chris McCormack’s feature ‘Love AIDS Riots’ in AM423). The action on this occasion was aimed at the private big pharma company Burroughs Wellcome, whose exploitation of a public health crisis caused the annual price of AZT to rise to $10,000, making it one of the most expensive drugs ever.

Small gains: Burroughs Wellcome lowered the annual cost of AZT by 20% to $8,000, largely due to the relentless pressure from ACT UP; Tate has replaced BP with international automobile manufacturer and shipping conglomerate Hyundai; Goldin’s protests have secured the divestment from Sackler by Tate and the National Portrait Gallery, in the latter case after the photographer threatened to withdraw her participation from an exhibition if they accepted Sackler’s £1m donation towards construction of (ironically) a new facade.

The history of all hitherto existing museum activity is the history of artistic struggle. I refer to the decolonisation of museum spaces, rather than simply divestment (see Lizzie Homersham’s ‘Artist’s Must Eat’ in AM384, for more on artist divestment campaigns), because the kind of demands being made by contemporary artists have broader historical stakes. As Mel Evans discussed briefly in her 2015 book Art Wash, the fact that Henry Tate & Sons and later Tate & Lyle’s fortune was amassed through investment in cane sugar plantations in the Caribbean colonies during the 1800s raises rarely addressed questions related to the kind of activities British cultural institutions, and many elsewhere, are built upon. This is the philanthropy complex, in which benevolence frequently masks a violent and exploitative past, and remains intrinsically a part of the postcolonial present.

This is not to say that institutions like Tate are not playing a significant role in rethinking under-addressed histories. As art historian Terry Smith has pointed out, the era of the mega museum has ushered in new and urgent questions relating to the way histories of modern art are discussed by bringing together practices outside the traditional Euro-American purview of painting and sculpture – though usually at locations within that domain. Artists such as John Akomfrah have created breathtaking works embracing post-colonial viewpoints. The Unfinished Conversation, 2012, for example, is a film essay that traces the life of the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall and his relentless interrogation of identity during his time in both Jamaica and the UK. The film is intersected by a history of migration, poetic redeployment of literary quotes, and the music of Miles Davis. Indeed, this work by Akomfrah is in the Tate collection and was last exhibited in Tate Modern during the height of the recent Windrush scandal, in the new extension’s former oil tanks.

Yinka Shonibare’s recently installed British Library is made up of wall-to- wall library books covered in brightly coloured Dutch wax-printed cotton textiles bearing the names of migrants and famous children of migrants, such as Winston Churchill, on their spines. Complete with tablet computers, the installation is intended to be a learning environment and to encourage debate concerning migration as a paradigm of modern culture, and probably the difficulty significant public figures in the UK currently have with the terms of colonialism. The fact is that the kind of access to information available in the digital age today has not necessarily shifted the quality of historically informed discourse in the public sphere.

A significant issue is not just the way institutions represent artists but also how they represent artists’ concerns and the discourses addressed in the work. Take, for example, the case of the ‘Hope to Nope: Graphics and Politics 2008-18’ exhibition at London’s Design Museum last year. On learning that the museum was hosting an event held by one of the world’s biggest arms companies, Leonardo, during the Farnborough International Arms Fair, several of the exhibiting artists and collectives chose to act (Artnotes AM419). Writing to the directors, they requested that their contributions be taken down: ‘We refuse to allow our art to be used in this way. Particularly jarring is the fact that one of the objects on display (the BP logo Shakespeare ruff from BP or not BP?) is explicitly challenging the unethical funding of art and culture. Meanwhile, many of the protest images featured in the exhibition show people resisting the very same repressive regimes who are being armed by companies involved in the Farnborough arms fair. It even features art from protests which were repressed using UK-made weapons.’ In organised action on 2 August 2018, a third of the participants removed their works from the museum’s walls under the supervision of curators.

The removed works then re-emerged in a counter-exhibition as part of Brixton Design Trail in September 2018, together with a host of other materials in the indoor bowling green at Brixton Recreational Centre. In this ad hoc space, well-known artists such the Guerrilla Girls (Interview AM401), Peter Kennard and Jeremy Deller were shown alongside lesser-known artists, their work fixed to the walls and fastened to Heras fencing. At a public discussion organised as part of the exhibition, designer Charlie Waterhouse spoke lucidly about a series of other peculiar experiences related specifically to the Design Museum episode. Among the details was the fact that none of the artists were invited to the event’s opening. When he finally secured an invitation, it turned out that the evening was aimed at the social circles of trustees. Peter Mandelson, cabinet minister under Tony Blair and supporter of the Iraq invasion, gave a speech that included a verbal attack on current leader of the UK Labour Party and long-term Stop the War Coalition member, Jeremy Corbyn. Shortly after Blair facilitated the catastrophic invasion of Iraq in 2003, Mandelson accused opponents of being ‘infantile’. This arrogant lack of self-awareness might, nevertheless, reflect the situation fairly well, insofar as a crucial question emerging out of recent initiatives is whether those in charge of cultural institutions are willing to understand the histories in which artworks and exhibited objects are engaged.

It is problematic in this respect that BP and other corporations still remain present in museums. The collective BP or not BP? has been at the forefront of challenging the illicit ties between culture and dubious organisations in a variety of contexts. Its activities have included a kind of neo-Brechtian guerrilla theatre-crashing at BP-sponsored Royal Shakespeare Company productions, and the performance of adapted verse calling out the multinational’s desire to frame itself as a supporter of British history and its continued legacies. Given BP’s origin as the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, a former majority state-owned company (as revealed by political scientist and historian Timothy Mitchell), and its anti-democratic pursuit of oil across the region from the early 19th century to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, its relationship to British history warrants scrutiny. There is certainly more to be said about the legacies of the British Empire, the Commonwealth and British international diplomatic missions, and about whose interests are served by such activities. It is precisely these concerns that have informed the collective’s creative interventions in museum spaces (see Colin Perry’s feature ‘Art and Oil’ in AM369).

At the National Portrait Gallery, for example, BP or not BP? staged a spoof awards ceremony outside the BP Portrait Award exhibition in 2017, awarding the Hypocrisy Award to the gallery because of its stated commitment not to accept sponsorship from oppressive regimes. Showing a painted portrait by Dale Grimshaw of exiled West Papuan independence leader Benny Wenda, alongside a film made by the latter with Raki Ap, the uninvited mini-exhibition addressed BP’s extractionist role in the most eastern province of Indonesia, which is having devastating effects on indigenous communities and their environment. Such creative interventions shed light on the way corporate strategies maintain ties to oppressive governments with shameful human and land rights records in a neocolonial context whereby the lasting impacts of the colonial era, as discussed by Achille Mbembe and others, is continued with impunity. That is, the neoliberal complex founded on the rights of financial accumulation over the rights of ecological sustainability and the interconnected livelihoods of people, bringing into focus continued exploitation as the price of so-called postcolonial independence.

Owing to their invested historical interests, corporate sponsors, such as BP, aim to appear in support of critical inquiry, framing themselves as part of the solution rather than part of the problem. In early 2019, BP or not BP? organised a protest at the British Museum, the largest in the institution’s 260-year history, that was aimed at the oil giant’s sponsorship of the ‘I am Ashurbanipal: King of the World, King of Assyria’ exhibition (Artnotes AM424). Around 350 people entered the museum’s Great Court on 16 February to protest that many of the museum’s objects in the exhibition were looted from what is present-day Iraq. Speeches, choral singing of ‘no war, no warming’ and carnivalesque performances alongside coverage online placed the collective’s initiatives in dialogue with other activists, including Decolonize This Place at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, for whom repatriation and reparations are linked to the call for a ‘decolonisation commission’, or radical provenance, which is intended to re-examine historic African art collections, offering an opportunity to properly account for the legacies of oppression reaching back to colonialism and slavery. Shared concerns include the lack of transparent information regarding the exact circumstances under which objects in collections were acquired.

Debates in the British Museum context have regularly been steered towards suggestions that Iraq’s current instability means that it is unable to preserve its own heritage, with little mention of BP’s interest in having continued access to the Gulf States’ vast oil reserves. Yet as the critical research group Culture Unstained has argued, the plundering of museums in Baghdad in 2003 and the destruction of objects by IS in 2014-15 were direct consequences of the 2003 invasion. At stake here is the rehearsal of colonialist rhetoric which bypasses the guarantees of nationhood at the level of cultural heritage.

Consider also debates concerning the ‘Elgin marbles’, taken from the Parthenon by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s and bought from then Ottoman-occupied Greece and sold on to the British government. Claims to keep them in the UK include the museum’s apparently legal purchase of the pediment friezes and sculpture, concerns that their removal might dent visitor numbers and an ambiguous argument alluding to the British Museum as safeguarding global heritage. Refusing the right of return, however, precludes the possibility that the repatriation of cultural objects will play a significant role in future reparations and progressive diplomacy. Resources are instead committed to maintaining neocolonial imbalances.

An additional component of the recent British Museum controversy included the organisation of the counter-exhibition ‘I am British Petroleum, King of Exploitation, King of Injustice’ at London’s P21 Gallery. Coinciding with the anniversary of the 2003 invasion, the exhibition focused on contemporary artists working in Iraq and its diaspora and contained works that addressed the country’s current state. For example, Khalid Tawfiq Hadi’s photographs taken in Basra during protests in 2018 showed continuing unemployment and the deterioration of public services 15 years after apparent liberation and subsequent transition to ‘democracy’. Remarkably, many of the images conveyed both the ruination of the city and the solidarity of its people within, whether in protest or in everyday convivial exchanges. In other words, the works framed a scenario in ways that did not feed into more conventional mediagenic portrayals of unruly masses, yet still pictured civic spaces that had been dangerously deprived of investment. Indeed, fitting with Mitchell’s reflections, these images may pose urgent questions regarding what western democracy looks like outside its home territories.

This last point is an important one. Small independent spaces and activist initiatives are contributing to the remaking of the histories of art and dissent. Significant media coverage of the ‘King of Assyria’ exhibition was accompanied by coverage of BP or not BP?’s creative protests, owing also to the artists’ persistent presence at this and other exhibitions. A further issue with the mega-institutional present, therefore, is its prominence in public discourse and by extension the kinds of activities and creative practices space is dedicated to. Goldin has certainly demonstrated that well-established artists can wield significant influence in holding institutions to account. The Serpentine Gallery used its exhibition of Hito Steyerl’s work to reaffirm that it had not accepted money from Sackler since 2012 (Artnotes AM426), although owing to legal reasons the Serpentine Sackler Gallery will retain its name despite Steyerl’s recommendation that it be changed. Steyerl and artist Andrea Fraser have been at the forefront of a new antithetical institutional critique in their respective practices and writings. Both have expressed concern over present-day patronage systems in the wake of the public sector’s dismantling, suggesting that the neoliberal sponsoring of critique advocates that private philanthropy is best placed to administer social and cultural discourse. That both artists have work in the Tate collection is nevertheless crucial and evocative, continuing to interrogate the figurative relationship of art spaces to the uncertainties of the public sphere after the first, second and, arguably, third waves of institutional critique. But what about activism and its relationship to the old stakes of art?

Perhaps intending to appease its systematic negation of climate issues after its 26-year BP sponsorship debacle, the artist Olafur Eliasson installed outside Tate Modern at the end of 2018 two dozen large blocks of centuries-old ice from Nuup Kangerlua fjord which had broken loose from an ice sheet in Greenland, each weighing several tons. Another six were placed outside the project sponsor’s HQ, the finance software, data and media giant Bloomberg, whose CEO is the ninth richest person in the world. According to the artist and his collaborator, geologist Minik Rosing, Ice Watch London aimed to communicate the effects of climate change by more direct experience. Eliasson wanted viewers to experience the coldness of the blocks and gain a sense of their historical weight while they thawed over a week, hoping to ‘inspire radical change’. His work is likely to have been enjoyed by many and potentially prompted private conversations regarding the reason for their presence. Yet to what extent his work critically informed such conversations is moot, insofar as their synecdochic relationship to heterogeneous effects of planetary crises was left unattended. Indeed, the Bloomberg News network frequently frames the developing climate emergency as a market opportunity. The artist’s insistence on direct experience over spectacularisation was only slightly undermined by the large number of cameras set up to record the melting blocks such that it was difficult not to view the cameras as components of the installation. The critique of spectacle is about more than the sensationalist image devoid of context. It is also about the nascent appropriation of discourses divorced from their epistemological roots. Unaddressed were the roots of environmental degradation in the very formation of capitalism which researchers have variously attributed to the establishment of colonies, mass transportation and to the industrial revolution. Further lacking was any reference or even measure of urgency comparable to creative movements such as Extinction Rebellion, whose highly visible and obstructionist activities specifically highlighting climate disaster have been taking place in the city since October (Reports AM427). Indeed, activist-artists are fighting to force the hands of power by interrogating issues of the past, in the interest of the present.

If mega-institutions have brought together histories of modern art and contemporary practices outside the traditional Euro-American purview, then they have done so predominantly at arm’s length, framing radical art politics as having happened either elsewhere or at another time. Tate has trouble with activism (see John Jordan’s ‘On refusing to pretend to do politics in a museum’ AM334). On 14 January 2012, Liberate Tate placed a 55kg block of Arctic ice donated by a researcher into Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Four masked figures carried the block from the Occupy encampment outside St Paul’s Cathedral. Their action was followed by that day’s Occupy London general assembly, which was held around it the ice. In response, the hapless Guardian critic Jonathan Jones suggested that Liberate Tate should ‘go and do something useful like join Occupy’. As Evans has pointed out, the events were obviously immanent. But, somewhere therein lies the rub.

Liberate Tate’s unauthorised performance, Floe Piece, was not stopped by Tate. But nor was it, or any other of their many activities, clearly credited as being ‘art’. The following July Liberate Tate also attempted to donate a wind turbine blade to the Tate collection, called The Gift, carrying it into the Turbine Hall as previously (see Maja and Reuben Fowkes’s feature ‘#Occupy Art’ in AM359). On this occasion it was taken away by the museum and apparently placed in storage. Yet if by chance it does re-emerge, under what circumstances will it be framed or credited as a work and will it have lost some of its antagonistic immediacy in BP’s absence? Conservative figures like Jones repeatedly advocate that contemporary politics should be absent from art while championing the representation of politics in safely established and temporally distanced Old Masters. What such figures fail to grasp is that the capacity of museums to represent and comment on current art and artists is flawed by the refusal to take note of their politically engaged contemporary activities. Tate and other institutions are potentially at risk of something similar by refusing to see activism as a serious component of contemporary practice.

The argument here is not that institutions become cathedrals to ‘relational aesthetics’ or prescriptive towards artists becoming social workers, circumstances that have been debated at length. Nor is it that artists simply redeploy traditional methods of working to reprise a status quo ante. Rather, the point is that artists and activists are interrogating capital and its pervasive role in cultural representation in formal and informal settings. Of course, it is in vogue to frame the spectre of imperialism as a hauntological antecedent to museums as monuments to a dreadful past. Yet leaving it there only partly responds to broader existential crises. What is more productive, in my view, is to foreground the role of artists and activists in challenging the interrelation of institutional and discursive framing of the past and present within current museum culture. It is, after all, these artists who have drawn attention to the duplicitous interlinking of neocolonialism and corporate patronage, and thus the necessity of framing divestment in the broader context of decolonisation. That is, insisting on radical assimilation as cultural capital, rather than expediency in the shadows of widespread discontentment and dissent. It is this spectre that haunts cultural institutions, rather than its antecedent, because it is impending, yet to fully materialise.

Activists declare that their alternative ends can be attained only via the redefinition of existing social and cultural conditions. Indeed, what activists are doing – what activism is – involves creatively interrogating hypocrisies as they exist, scrutinising the foundations of modernity and the future of its institutions, with an intention to occupy and reclaim.

They have a world to win.

Tom Snow recently completed his PhD in the history of art at UCL.

First published in Art Monthly 427: June 2019.