Feature

Curator and Artist

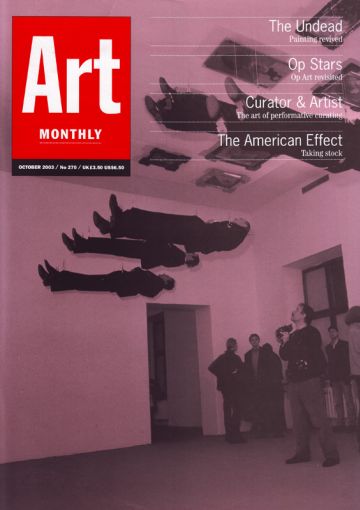

Alex Farquharson on the new alliance between the performative curator and the relational artist in the postproduction of art

It’s not often these days that you find a critic brave or foolish enough to attempt to define and name a whole set of contemporary practices. Nicolas Bourriaud is one such, and the titles of his two recent publications Relational Aesthetics and Post production1 provide a handy means of identifying a field of activity that has been around for the last decade. Previously that field could only be indicated by reeling off a set of proper names – Liam Gillick, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Pierre Huyghe, Jorge Pardo, Philippe Parreno, Rirkrit Tiravanija – adding ‘et al’ to signify their ubiquity in this area of discussion.

It seems that both these eponymous neologisms had been circulating for some time among these artists, as well as the curators they associated with, and that they had come to mean a range of things. When I began reading Bourriaud’s books I was struck by the narrowness of his application of both terms, given the mutability of practices such as Gillick’s, Gonzalez-Foerster’s, Pardo’s and Parreno’s. Particularly striking, given that he is a curator, is Bourriaud’s failure to address the ways in which this group has moved in on what has traditionally been the curator’s domain, and how these encroachments relate to and have contributed to the development of what has become known as ‘performative curating’ (see AM269). It seems to me that the terms ‘postproduction’ and ‘relational aesthetics’ are especially evocative of this aspect of what these artists do.

‘Relational’ in Bourriaud’s discussion of ‘Relational Aesthetics’ is used in a social sense to identify works that incorporate viewers or groups of people in the form of the work itself, as epitomised by Tiravanija, who often includes ‘lots of people’ as a material on his exhibition labels. Practices like Tiravanija’s pre-empt and literalise the postmodern principle that an artwork only exists at the point of reception. At the same time, the transformation of spectators into participants, or consumers into producers, is a potentially political move harking back to the Situationists. ‘Postproduction’ is another way of considering the same practices, this time based on a conventional understanding of appropriation and the readymade (ie the refutation of originality and authorship), the distinction being that Bourriaud resituates these familiar discussions in a social and technological field, rather than the domain of images and objects. Gillick’s solo exhibition at the Whitechapel last year offers a useful means of exploring the limitations of Bourriaud’s application of ‘relational aesthetics’ and ‘postproduction’, especially since it is so recent.

Allusions to conferences, discussions and negotiations in the titles of Gillick’s platform and screen pieces suggest that his works too are completed by the activity of viewers: Twinned Renegotiation Platforms, 1998, for example, ‘provides a place where it might be possible to reassess the idea of planning when it moves into the hands of speculators’.2 However, given the reductive language of the structures, one can’t help feeling the titles are knowingly overdetermined. The operative phrase here is ‘might be possible’. Whereas Tiravanija can reasonably expect his visitors to eat his noodles, it is unlikely that Gillick’s audience will do his reassessing. Instead of real activity, the viewer is offered a fictional role, an approach shared by Gonzalez-Foerster and Parreno.

Gillick’s use of ‘relational’ and ‘postproduction’ differs somewhat from Bourriaud’s in other ways. In an interview at the time of his Whitechapel exhibition he spoke to me of the absurdity of being asked to exhibit a large number of his recent platform and screen works. I was slightly taken aback. Wasn’t he simply being offered a more or less conventional survey exhibition? Why should that invitation be so off-the-mark and problematic? Why so ungratifying? ‘Normally my work is very relational’, he went on. ‘The way these platforms work well is in relation to other things around them. All the work is made with somewhere in mind, so what do you do when you take the work out of these situations and put them together? ... The platforms work best in places that aren’t terribly good for art, in situations that are architecturally quite problematic ... I needed to address this idea of relational aesthetics and relational ideas, without any relational devices, anything to refer to, any other artists’.

Gillick’s reasoning seems perverse. Most artists like positioning their work on large empty walls and find it easier interrelating their own work than relating it to other people’s. With Gillick the reverse is true, to the extent that another artist’s work might complete his. To get around the problem of the screens and platforms not having any context to play off, he devised an elaborate wooden display structure that most of the screens and platforms docked onto. He went as far as claiming in my interview that the structure ‘works as a kind of title’ or is ‘a complicated way of finding somewhere to put the title labels’. Perhaps this is what Gillick means by ‘postproduction’, a term used in his writings for some years. If production is what gets made in the studio (or elsewhere), then postproduction could be what happens when those unfinished elements are mixed or edited in the gallery (or elsewhere).

As part of the Whitechapel exhibition, Gillick replaced one of its internal doors with one from Le Consortium, Dijon, which he ‘renovated’ in 1997. Renovating doors, designing display systems and devising labels is usually the domain of the curator and the institution in general. Normally these activities belong to the framework that surrounds and mediates the work, not to the work itself. But as Maria Lind and Soren Grammel point out, ‘contemporary art has become increasingly involved in mediation as a theme or operates directly with mediating strategies’.3 Examples they give include Andrea Fraser’s guided tours of museums and Adam Page’s conference hall at Documenta X.

If all these strategies sound familiar it is because in a sense we’ve been here before. In the 60s and 70s it was called ‘institutional critique’. Examples include Michael Asher taking down the wall separating the exhibition space from the dealer’s office at the Copley Gallery in Los Angeles in 1974, Daniel Buren sealing off the entrance to Galleria Apollinaire in Milan in 1968 with his signature stripes, and Hans Haacke’s parodies of didactic display panels which exposed the unethical interests of art sponsors, The main difference between the institutional critique of these artists and the ‘mediating strategies’ of artists today is that the former still tended to regard the framework of the institution as anterior and hostile to the work of art, and therefore something to confront or shut down, while ‘postproduction’, of the kind Gillick practices, insinuates itself within the mediating systems of the institution, implying that the two are indivisible. This implication is especially strong in institutions where curators are already actively deconstructing those same frameworks. Some ‘performative curators’ even understand what they do as a kind of art practice: just as there are artists ‘increasingly involved in mediations’, so there are ‘mediators who understand their work as aesthetic productions and develop projects or public formats that themselves assume “artistic” strategies’.3 In these contexts the division of labour between artist and curator is all but erased: the performative curator and postproduction artist collaborate in the business of deconstructing the mediating systems of the exhibition and institution.

Often with group exhibitions curated along performative lines the artist-curator hierarchy is maintained, if not extended. When curators seize the conceptual ground usually occupied by artists, this places artists – often in vast numbers – in the subservient role of interpreting and delivering the curator’s a priori, overarching premise. The hierarchy is dissolved when curators invite artists to postproduce their exhibitions. Lind’s ‘What If: Art on the Verge of Architecture and Design’ at Moderna Museet, Stockholm in 2000 is an important example. The exhibition evolved from a consultation process with a number of artists participating in the exhibition, one of whom, Gillick, acted as its ‘Filter’ (as opposed to its co-curator). Works by 17 of the 21 artists shown within the gallery space – many works were shown elsewhere in the building or in other contexts altogether – were grouped together in a tight geometric cluster, evoking a cityscape, while the other four had the run of three-quarters of the space (Gonzalez-Foerster, Pardo, Rita McBride and Martin Boyce). The lighting went through cycles simulating day and night, as is common in the retail areas of casinos in Las Vegas. These two gestures would have come across as an abuse of power had the curator done them. As an artist operating in the grey area between art and curating, however, Gillick had a special kind of licence. The same is true of Pae White, who designed the catalogue as a series of loose pages in a box that can be re-assembled in whichever way the owner wants. The catalogue, which incorporated other print material such as the poster and exhibition guide, is both mediation and Pae White multiple. The outsourcing of curatorial responsibilities to artists made for a radically deconstructed show.

The Munich Kunstverein, where Lind is now director, has begun extending this principle by involving artists in the infrastructure of the institution. One of the ways this has been achieved is through so-called ‘Sputniks’: artist-advisers who have an extended relationship with the institution over a three-year period, ‘contributing questions, critical commentary and ideas which will hopefully affect in a literal way how Kunstverien München is operating’.4 The resulting art works can adopt any format the artists like, be it an exhibition, publication, conference or some other output. The first ‘Sputnik’, Apolonija Sustersic, has re-conceived and redesigned their lobby, while the second, Carey Young, is ‘developing a new work which functions within the [Kunstverein’s] communication structure’.4

This new alliance between performative curators and relational artists (in the Gillick sense) is resulting in much-needed challenges to the stale conventions of exhibitions and museums. At a time when museums are increasingly transforming themselves into business enterprises, tourist attractions and family-friendly learning centres, it is vital that these explorations continue.

The down side, as I see it, is that curators interested in dealing self-reflexively with the structures of mediation inevitably end up privileging and creating an artificial demand for art practices engaged in those same questions. If performative curating developed as a response to what the first generation of relational artists were doing, it’s now in danger of prescribing what the next generation does. Undoubtedly there are a lot of interesting artists working this way, especially on the European mainland and in Scandinavia. The problem is that there are a far larger number of interesting artists who aren’t. You don’t get a sense of that from some performative curators: like retrograde avant-gardists they’ve seen the future, and that future is relational.

When it comes to exhibitions of finished objects (paintings, sculptures, photographs and films, for example), efforts to foreground the curatorial frame often end up being clumsy, interfering and trite. The seating in ‘Urgent Painting’ (curated by Laurence Bosse, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Julia Garimorth at ARC, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 2002) was colour-coded to indicate which adviser had selected which artist, and is a case in point. The strength of an exhibition like ‘Urgent Painting’ should have derived from what the artists had done in the paintings, not what the curators were doing with the furniture.

It may just be that for most art the conventions we’ve arrived at are the most appropriate. That’s not to say we should be blind to their operation nor unwilling to experiment with new techniques, it’s just that having interrogated these conventions we should be prepared to concede that the alternatives are less desirable. The results might make for a slightly boring and nebulous conversation on the level of curating, but it might make for a more exciting experience on the level of the art. From Minimalism onwards, it is often the most radical art that requires the least from curators, precisely because these artists have occupied the physical and interpretative frames that previously belonged to the institution.

The aversion to so-called ‘finished’ art works, whether they be finished on site or in the studio, often betrays a rather naive and over-literal interpretation of the death of the author / birth of the reader maxim derived from Roland Barthes. All works of art, especially good ones, are open systems that the recipient reformulates in his or her own way at the point of reception. A supposedly finished work will be reformulated as often as a so-called relational or unfinished one. Nicolas Bourriaud quotes Jean-Luc Godard saying as much: ‘If a viewer says, “the film I saw was bad”, I say, “it’s your fault; what did you do so that the dialogue would be good?”’5

1. Nicolas Bourriaud, Esthétique Relationnelle, Les presses du réel, 1999, and Nicolas Bourriaud, Postproduction, Lukas & Sternberg, New York, 2003.

2. ‘Liam Gillick’, Octagon, 2000, Cologne (eds Susanne Gaensheimer and Nicolaus Schafhausen), p96.

3. Søren Grammel and Maria Lind, ‘Formats that Transport Art’, www.kunstverein-muchen.de.

4. Søren Grammel, Maria Lind and Katharina Schlieben, ‘Editorial. In Place of a Manifesto’, Spring 2002, www.kunstverein-muenchen.de and Drucksache, Spring 2002.

5. ‘Postproduction’, p29.

This is the second part of a feature on current trends in curatorial practice. The first part appeared in the previous issue (AM269).

Alex Farquharson is a freelance curator and writer.

First published in Art Monthly 270: October 2003.